Adapting SITCAP-ART: The Story of One Program’s Journey in Group Implementation for Transformative Results

This paper explores the adaptation of SITCAP-ART to fit needs and aptitudes of at risk adjudicated youth in a particular intensive after care program. After describing the program, population served, and problems with prior groups, it explores the process this therapist went through to awaken to SITCAP, and how the curriculum was designed to fit our clients and program. It specifies how we ‘sold’ the group to others, our results, outcomes, and continued challenges. It is intended to be ‘user friendly’ in the hopes that other practitioners will learn from our experience and borrow any or all ideas for their own programs and mental health treatment services.

Background

Our program, named Reentry Services, provides intensive after care (IAC) treatment in the form of groups, individual therapy, and case management/CPST to at-risk adjudicated youth returning to the community after a residential placement for their juvenile offenses. The youth are court ordered to attend as part of their parole or probation terms and receive our services over a range of 4-8 months. The majority of youth are African American from poor neighborhoods in urban Cincinnati. They come with generational, developmental and/or complex trauma histories characterized by abuse or neglect in childhood; school behavior, truancy and academic problems; separation/abandonment from incarcerated or murdered family members, particularly fathers; poverty or financial instability; and high exposure to community violence, drugs, guns and death. They are most frequently diagnosed with PTSD or other Trauma indicators, ADHD, Conduct Disorder (D/O), Substance Abuse D/Os (marijuana being the highest prevalence of use), and often Borderline Intelligence (from low IQ scores.) Other common but less frequent diagnoses are: Reactive Attachment D/O, various Mood D/Os, and Learning D/Os. Occasionally but rarely do we have Bipolar D/O or any form of psychosis.

The youth also experience long separations from families and their communities after multiple placements that often accumulate to years, based on their repeated adjudications and probation violations. In residential placement, they are subject to group programming developed by juvenile justice (JJ) academic organizations, with very structured curriculums that are cognitive behaviorally based to correct criminal thinking, stop substance abuse, and manage anger. Occasionally mental health treatment is provided, and trauma specific therapy is rare.

In our phased, step down IAC program, youth typically attend 3 groups a week the first month, then step down to two for another two months, then remain with just individual therapy and case management for their last ‘phase’. Since the program’s inception in 2009, the three groups have varied in definition and content, with titles such as ‘Community Life’, ‘Relationship Group’, and ‘Substance Abuse’ groups. They were designed to use CBT and motivational interviewing interventions that built on the treatment concepts they learned at their placements, assisting them to internalize the skills as they transition to the community. As one of the therapists who developed the curriculums and facilitated the groups throughout the program’s first three years, we tried an array of formats, ranging from very structured to more open, client led groups. We learned that groups work best ‘in the middle’ of the spectrum, with enough structure to provide direction and focus, but loose enough to allow the client to engage in what we call ‘real talk’, honestly sharing about their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors since their return. We also had some success using creative, right-brain, fun activities to keep groups interesting and dynamic, while keeping a fast pace for fidgety and easily distracted youth.

The Problem

When the youth arrive at our program, they are burnt out on groups. They are tired of just talking and doing worksheets, with lots of rules to keep behavior in check. Positively, they are equipped with CBT skills that they learned in placement, yet they have not been able to practice or use them in real life. Then typically they get exposed to real life traumatic situations anew and/or triggered upon return to old environments and, alas, they are unable to use their new found CBT skills. In other words, their prefrontal cortex is not able to work with the trauma affected, unhealed parts of the brain. So essentially, the thinking based skills go right out the window, leaving probation officers and treatment providers baffled. This restarts the punitive cycle, as triggered youth with no trauma healing go AWOL, commit new offenses, smoke marijuana, struggle in school, and ‘act out’ emotionally and physically. The courts give citations and violations, or send them to new placements. Meanwhile, we scramble to add more services, particularly high dosage of substance abuse services. We find ourselves saying things like, ‘you had all these great goals and seemed so motivated to change, what went wrong?’ Or, ‘Why aren’t you using the skills you learned in placement?’ In other words, ‘what’s wrong with you?’

Awakening to SITCAP

I remember learning briefly about CBT trauma therapy in grad school, and felt immediately after starting work at our agency, that we were missing out on addressing trauma more directly. Often I would debate with our service providers with long histories in juvenile justice, about the discomfort I had with not addressing feelings thoroughly enough, as this also is an important component of CBT I observed was consistently short changed. I also read about how the JJ residential programming and our IAC model was based on the adult criminal system, which was created for anti-social adults, emphasizing correcting anti-social beliefs and attitudes. It was missing developmental understanding, compassion for what the youth had experienced, and was not sufficiently strength based.

It was about two years ago that I was able to attend the initial SITCAP trainings. I remember thinking that finally, here is a model that has the right ‘lens’ for seeing and understanding our youth. There are interventions that fit them, focusing on healing the brain and body, and addressing more than the logical, thinking part of the mind. The whole person is addressed – mind, body, and spirit. And the fun activities we tried to fit in awkwardly to our groups are an essential part of the healing and done with intention, leading to the CBT part of reframing the story for hope, and moving from victim to survivor. We decided we would replace our ‘relationship group’ with a SITCAP/trauma healing group (as well as train our therapists and CM’s to incorporate SITCAP interventions in their practice, but this is not a subject of this paper.)

Big ‘Aha’

So while the overall model of SITCAP, the themes, the treatment process, and the approaches all made sense for our population, I concluded that the SITCAP-ART curriculum would not work as-is for our group. First, the language often centered on specific traumatic events, and our youth could not identify these events, indeed they don’t think of traumatic experiences as particular events, necessarily. This is because there are so many of them, they don’t remember them, or they don’t want to be directly asked about them. Second, I felt the language and pictures were too young for our youth who, though may be behind in developmental maturity, talk with more mature language, and are very sensitive about being talked to like they are young. Third, I felt the activities did not adequately reflect the black, urban culture, and that this would be key to connecting with them in a trauma group.

Thankfully, I had two ‘aha’ moments at this point. First, our agency trainer and expert in SITCAP consulted with me, and assured me that the materials were just a starting point, and that I should find a way to adapt the materials to our youth. This was liberating, I just didn’t know how! The second, ‘aha’ came when I took TLC’s online course called ‘Breathe, Rock, Draw’, by Barbara Dorrington, MBSW, MEd, CTC-S. I was fascinated by how she organized and structured activities for her classroom into three areas: breathing exercises, rhythm routines, and drawing/writing. It included positive affirmations, warm ups, and encouraged creativity in identifying the activities that could be used in the three areas. I started to think about how the exercises energized or calmed, both types being needed by our youth, covering the range that was needed to address hypo and hyper arousal. Thus began a kind of creative brainstorming over several weeks, laying out ideas and talking to others, until finally it hit! We could redesign our groups to incorporate both active and calming activities, while also addressing the model themes and providing narrative reframing.

Group Redesign

We would structure our groups around these three categories: Mellow, Move, and Make (MMM). We would end on a positive or ‘Up’ note each group as is important for the model. Each group would have a SITCAP theme e.g. anger, hurt, victim/survivor. This way, we would be following the overall progression of the model which is so important to address the trauma themes and get to the narrative reframing, but also allow us to actively engage in emotional management, thereby reducing traumatic stress symptoms. We would have psychoeducation pieces to assist facilitators in being deliberate and aware in the healing work. We would invite speakers occasionally, to bring the themes and activities to life. We kept our group norms, but we added one to allow members to find ways to self regulate and encouraged this via the norm: ‘Find & use what you need to stay and be part of group: mandalas, doodling, stress balls, stretching’. See the attachments titled ‘Self Group Design: Mellow Move Make’ and ‘Self/MMM Group Introduction’ for more thorough descriptions.

We use a matrix approach by adding various activities in each of the three categories and for each theme. This allows flexibility for the facilitators to alter activities to fit the group, and keeps the groups from getting repetitive (as some clients end up repeating groups over time). The activities are designed to be more culturally relevant, referencing current events, contemporary African American urban culture, and common themes that reflect attitudes and beliefs we have learned over time from our youth. See the attached group example titled ‘Self/MMM Group Example – Anger/Love.’

We also kept our Community Life CBT and AOD groups, although eventually we ‘wrapped’ SITCAP around them, and continue to evolve them this way.

The Sell

When we began using SITCAP in our agency, there were just a few of us practicing with one SITCAP experienced and certified trainer to assist as we gained practice using the tools and model in our own service areas. Not surprisingly, we met some resistance and skepticism in the agency, as happens with new or different approaches. I particularly felt this in Juvenile Justice. So it was important that I ‘sold’ the new group to my management in a way that assured we would be covering the critical treatment concepts, while improving the way we were doing so.

Our proposal was based on the need to solve the problem of client burnout, by creating groups that provide a new experience from what they have known. We proposed the SITCAP approach could make groups transformational and challenging, which was everybody’s goal. Importantly, we were not introducing new or contrary treatment concepts, we were simply reframing treatment concepts that we have always used, bringing them to life with SITCAP, and bringing in a couple of new concepts for trauma education and healing. We would be improving our ability to provide a safe environment that is more resilient to negative peer influences. By tackling exposure to traumatic events we proposed it would make it easier for the youth to make connections to their offending behaviors. We also could finally bring in health & wellness psychoeducation for certain topic areas that had been a stretch to add in the past, like sex education and sleep hygiene, which began our foray into the mind-body work.

We vetted the group with our agency’s trauma practitioners. We did this by having the practitioners experience being the group members, with us facilitating. This was extremely helpful, for we got some great tips, plus it helped validate our curriculum.

Our director asked for how we could sell this to the courts, and we used this: We teach our youth important skills while they are in their placements for their crimes. Many accept responsibility for what they have done and want to change. However, when they return to their stressful environments, they get triggered and/or emotionally dysregulated again. This shuts down the thinking part of the brain, so they can’t use the skills. We need to heal and regulate emotionally, calming down the brain, so that the CBT skills can be used and internalized.

We also used brief surveys the youth filled out for the end of the old groups and the beginning of the new, that confirmed positive trends needed to continue forward with implementation.

We were now ready for ‘prime time’, and started the groups in October, 2014.

Our Results

A year and a half under our belts, here are our key learnings from conducting our adapted SITCAP-ART group:

- These tough, ‘street smart’ youth do the ‘corny’ sensory activities! My biggest worry was that these young men would refuse to do the activities we offer. However, we frame as asking, not demanding, asking that they just try or sit respectfully as others try, and explaining these are things we do ourselves that many adults do to take care of their stress. We are constantly surprised at how courageously these youth jump in and try activities including yoga postures, breathing techniques, guided meditation, lavender sniffing, mindfulness walks, singing ‘Hallelujah’, affirmations, and Native American chants about forgiveness.

- ‘Real talk’ has increased. Our desire has always been to allow the youth to discuss the real problems and struggles they face upon return to the community. However, we were afraid we were glorifying crime and violence, and would not allow talk of gangs or guns. With the SITCAP group, we had to accept that when we ask a youth to draw about their biggest worry or fears, these things will emerge. These are the traumatic experiences. We had to allow them to be put on the table, and honor their realities. We had to hear about what underlies the fatalistic attitudes and beliefs. We became witnesses to the struggle. So the youths drawings often show guns, contain curse words, street slang, and other disturbing things. Many of our youth write rap or record it in studios, so we invite them to share and often it is explicit, but underneath are the message we discover together about difficult life experiences and deeper feelings, like abandonment. We had to get over our own biases, and allow the youth to share their own interpretation of their experiences. Of course the goal is to get to the hopeful reframing and normalizing, which we do. But we learned to allow the time for this to happen vs. forcing it to happen on our terms.

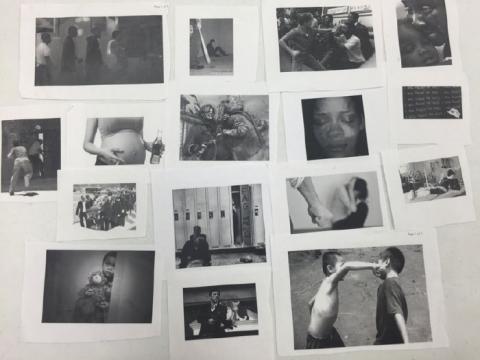

Exposure is helpful for our youth. My prior understanding of trauma therapy was to be wary of exposure and triggering. And we do worry, and triggering does happen. However, it was happening anyway, because these traumatized and daily stressed youth were getting triggered all the time, including in our program, by for example, the tone of voice used by an aggressive Probation Officer in a team meeting. Our challenge was to provide safe containment and emotional management skills to manage and reduce their trauma reactions. Revisiting traumatic experiences was already happening sporadically in past groups, as things like shooting deaths were brought up and discussed as group members (and staff) became more comfortable. So we came up with a safe way of initiating exposure: displaying black and white images (from stock images on the internet), of various traumatic experiences that we had heard youth describe over the years. See the attached ‘Self/MMM Group – Tough Times Table’ for some of the images used. Then, when we do the ‘road map to the past’, we ask youth to visit the ‘tough times’ table and choose images that depict bad times they have experienced. If they are not comfortable, they can choose images that others might find difficult. This puts them in control and they don’t have to share their choices with the group unless they want to. We found with this technique, more traumatic experiences are revealed than we had ever heard in the prior 3 years of groups, particularly bullying and domestic violence.

- A trauma informed environment is needed. From the beginning, we designed various sensory elements into our program’s environment, like cooling wall color, welcoming décor and art, aromatherapy, and youth’s mandalas on the walls. We try to surround youth and staff with an array of sensory stimuli and activities, such as comforting food, music, hand ‘fiddles’, games, and multi-media technology. We created a relaxation room for therapy and ‘chilling’ when clients need it. We also are more attuned and aware of triggering to be able to proactively help youth anticipate and manage feelings and behaviors as they emerge. We are more often checking in on the body and reminding them of their emotional management tools, thereby promoting a sense of safety.

- The walls of anger come down. I used to hear, ‘I don’t care’, ‘I don’t have feelings’, or ‘my only feeling is anger.’ Conversation was dominated by prison and ‘street’ talk. We thought that these youth were emotionally incapable of empathy. This was incorrect, we just weren’t finding ways to open up the other emotions. Now I hear, ‘I am a loving person’, ‘I am glad to be alive’, ‘I am afraid of these streets’, ‘I worry that I won’t be able to get out of my hood and make it’. We could never get the youth to acknowledge fear previously, and now it is sometimes said, and often depicted in drawing, etc. The sources of anger are also more apparent. For example, feelings about racism, oppression, conspiracy theories, and cultural taboos, are more explored and debated. Feelings allow these youth to debate and discuss their opinions in a deeper way with each other than before. We have even been able to discuss spirituality more. One group ended with a youth who insisted, after getting permission from the group, in leading an affirmative prayer for all members.

- There is more safety and trust. You can feel it. This is subjective for us as we do not measure this directly. Beyond the improved outcomes, there is a sense that permeates the program that youth are more relaxed, less apt to lash out in anger, more able to focus, get to the ‘real talk’ and, essentially, show their vulnerability. This affects the staff as well, creating a greater sense of safety, reducing vicarious trauma. There is a greater use of humor and a sense of fun. As a result, some of our toughest youth continue to come for services, even when they are confronting death of peers, revenge urges, and drug relapses.

Outcomes

Youth are completing the program more successfully, in terms of mental health improvements, getting off of parole/probation, and making gains in life domains, such as education and employment. Our biggest testament is that we have more youth who don’t want to leave our services when they have completed the program. And more come back after they are done with services to attend our prosocial activities or just visit. Our program implemented outcomes tracking after the start of SITCAP, and we made several program improvements (like adding prosocial events and job readiness groups) that make it difficult to isolate the impact of SITCAP. However, we know that the CANS (Comprehensive Needs & Strengths Assessment) outcome tool we use at our agency indicates that we have been consistently reducing needs and increasing strengths for the youth who receive SITCAP interventions (group and individual therapy). We are currently in the process of adding modules to our outcome tool so that we can measure post traumatic symptom changes.

Challenges

Not everything we set out to implement has happened, and there are still areas we continue to struggle. Here are the challenges and where appropriate, plans to improve:

- We are not getting to the narrative, at least not directly. It has been difficult for us to be disciplined about saving client’s work from group and individuals, taking pictures of things that cannot be saved (like clay sculpture). We get behind and then we end up with a pile of drawings, poems and pictures that are not organized. Individual therapists reframe and discuss the narrative sporadically, but not in a direct, deliberate way. In other words, we are not getting to the ‘story’ as we set out to do in our group design. The one time I was able to do this more directly, however, the results were impactful, so we need to strive for this. Our plan is to get there is two-fold: 1) implement ways to make it easier for us to save and use the work; and 2) do more direct psychoeducation and expectations setting with treatment teams (clients, families and the courts) to lay out the model in user-friendly terms. We are currently developing a set of handouts for clinicians to use during intake and initial services.

- Therapists are not always comfortable with the mind-body work. It was relatively easy for me to begin using various mind-body and other sensory interventions with clients as I am an artist, and practice yoga and mindfulness already. It was a challenge for me to adapt the practices to our adolescents, but it was just a matter of jumping in and finding the right language. I built the interventions into the group curriculum and then taught them to my co-facilitators over time. However, some therapists are simply more comfortable with talk therapy, and do not have the aptitude for the sensory interventions. For example, in group, I find I am leading guided meditation as I am more comfortable and experienced doing so. To continue moving forward, I am encouraging our clinicians to develop their own experiences and practices so that they can empower our youth to use these skills based on their own practice of the mind-body activities. I also would like to develop a half day training focused on mind-body activity learning and practice.

- Triggering, dysregulation, and victim problems still occur. Our highly traumatized youth continue to have post traumatic stress behaviors and attitudes that disrupt and derail groups. Part of this is the nature of rotating member groups, which is the way our program operates. There have been many times that group is feeling safe, cohesive, and engaged in the activities, but then a new member appears and we destabilize into chaos. Or a traumatizing event happens to a stable individual and he has a setback. A hypo-aroused, dysregulated group member can disrupt and interrupt everyone. If the group members aren’t able to resist, they all get that way. Alternatively, if we get a strong leader personality that is highly traumatized and anti-social, others get intimidated and fearful, and we don’t get to the ‘real talk’. Members suddenly begin to dredge up ‘criminally minded’ beliefs and engage in ‘street talk.’ Others disengage completely or lapse into generalized ‘treatment talk’. Sometimes an especially vulnerable youth is alienated by the group. Our solution as facilitators is to step back and focus on the group process of building cohesion, and the curriculum frankly, becomes secondary. An idea we have considered is to create a separate step down group for those ready for survivor/thriver and narrative reframing. However, we don’t have the staff or youth numbers needed to set up this group.

- Keeping sensory and self regulation materials stocked is not easy. We try to keep our supplies stocked, but things disappear or get destroyed. ‘Finger fidgets’ get deflated, objects break, silly putty goes missing, food gets spilled and wasted, markers dry out. I don’t think our youth are intentionally ruining, but these high energy, stressed out young men are especially hard on things! It’s hard to find time then to get to the dollar and craft stores to keep up with replenishing our materials. And like most non-profit agencies, we have budget constraints. It has helped to bring in outside guests to lead creative activities, as they bring supplies that we reimburse. However, this takes planning and logistics to arrange, and it has been difficult to find guests that can handle our youth in a trauma informed manner and be reliable.

Conclusion

After running our adapted SITCAP-ART groups for nearly a year and a half, we have learned a lot about how to engage our youth in the trauma work, that is such a critical part of their mental health and life functioning. The work is exciting and challenging. However, I believe we are about halfway to where we could be in service delivery and the organizational commitment to trauma informed care. There are so many opportunities left for us to improve our trauma sensory interventions, deliver more components of the model, and to create a safe, trauma-informed environment. As a supervisor and therapist, my passion is to continue training, influencing and encouraging those within our agency, our partners, and the broader community to embrace sensory based trauma healing.

Self Group Design: ‘Mellow Move Make’

Agenda:

- Review group norms & last week’s group

- Prosocial news & Announcements

- Topic of the day: Write on the board

- Mellow – relaxation exercise

- Move – physical activity (walk, get up and do something, role play)

- Make – draw, write, listen, create something related to topic of the day

- Review of group

By the end of this group, members will:

- Reduce trauma symptoms

- Reframe their story in a positive, healing way

- Be less stressed, more motivated and hopeful about life

- Manage emotions better and able to feel & express healthier emotions

Topics: seven that rotate and new member can enter at any time + 2 to 3 speakers/activities

- Anger/Love

- Worry/Fun

- Guilt/Freedom

- Reactions/control

- Victim/Survivor

- Hurt/Caring

- Values & ID

Speaker 1x/month – stories of transformation – volunteers from the community to do ‘art’ projects.

My story: 15 minute presentation in any group, after member completes the six. Can be done in individual therapy as an option. Creations from each group (and individuals) are building the story. Member works with therapist to review and assemble, maybe put together into 1 story. Options to convey: graphic novel, self portrait, poem, etc.

Group structure: Every group goes through Mellow, Move, Make, and ends on Up note. Psychoed (PE) is used to make connections at end and review before next group. These ‘buckets’ can be reordered for flow. Most groups have a second set of M’s for a different concept so there is plenty to fill up a group. If not all are addressed, make sure we end on an Up.

Facilitation: Content of each agenda item are color coded (PE orange, Think yellow, Feel blue, Act red, Up green) on index cards to allow a less intrusive and more natural facilitation of group. Content is short as it assumes facilitators are well versed and skilled at bringing the treatment concepts to life in group. Allows containment and structure for safety and interaction by being less scripted and less rigid in format. Also, allows group to create the pace and go deep if it can, or move on more quickly if the group is not ready or able to (which happens with unsafe or new/forming groups). Question using TLC/SITCAP method – third person, not interpreting. Remember, the trauma healing and emotional regulation may be happening without verbalization, as it is happening with the sensory activities.

Self/MMM Group Introduction

Why this group: Young men who have a past with juvenile crimes and placements usually have had a tough life. This group is about respecting your tough life, because it helps to move forward. For some, there has been a lot of trauma*, and this group helps with that as well.

Goals of Group: Be heard & understood on your own terms. Handle your emotions (e.g. anger) and stress better. Be more motivated and excited about life. Learn more about yourself and who you want to be.

What you should expect: There is less thinking and more doing. The skills taught happen as part of the group work. Sometimes we get corny. If you have an open mind and work at it, you will have a different experience than other groups.

Presenting your story: You will put your work in a folder with your name on it so you can remember everything you created in group. We will take pictures of those things that you can’t keep or put in the folder e.g. clay, pictures from tables. You will be asked to present your ‘story’ by the last group (11 groups). Your folder will help you do this.

*About Trauma

A traumatic event is when something frightening or dangerous happens and the person doesn’t have control over it. Examples: death, abuse, neglect, car crash, parents separate; family member leaves; shooting; bullying. Even if the person was responsible, you can you still feel bad afterwards and it can affect you. Also includes stressful life situations, like not having enough to eat, moving all the time, changing caregivers, a parent with addiction, homelessness.

It becomes trauma for a person when the brain and body get stuck in defense mode, still reacting as if there is danger, long after the event is over. This is because hormones get released when the senses (hear, see, touch, smell) get triggered by cues from the past. The body believes it is still in danger, even if our thinking tells us otherwise. Over a really long time, we believe that danger is everywhere. No one can be trusted. Life is hopeless.

Drawing: However you draw is fine as this is not about skills at drawing, but helping to tell a story or get across your feelings in a different way than just talk. A picture tells a thousand words. Here are some drawings by other teens who agreed to allow us to share their drawings with others. You can see there are rough sketches and stick figures.

Bullseye of sharing: You may want to start out less personal – movies, books, stories, your imagination – to do an activity. Over time as you get more comfortable, we see people do more about themselves and their own experiences. We expect this. It means if you are new, you may be surprised at how much people are sharing. If you have been here awhile, you may remember where you started. We are all in different places with our stories and that is ok.

Choice: you can decide not to do something. It is up to you. We ask that you just tell the group this, then you can sit quietly.

Self/MMM Group Example – Anger/Love

Mellow –

- First rate anger 1-10 to yourself. Guide through a progressive muscle relaxation. This is a great way to relax before going to sleep, especially when your body is still keyed up.

Make –

- Visit the ‘tough times’ table. Pick images that make you angry and bring to table. There is also clay in front of you, as a way to take our anger out safely. Tell us what you are comfortable sharing about your pictures. May we ask questions (use third person)?

Move –

- Make a list of ‘Things that Tick me Off’ (what you are most angry, frustrated, annoyed, impatient). Take pictures. Stand up. Tear up at least 20 times. Rate anger 1-10.

Up –

- Video Spokenword about anger & frustration with the world, and a return to hope and self via LOVE. Rate anger 1-10. Take pictures of clay. http://youtu.be/BzV1FzixSmw

Make –

2.Listen to 1st half of video interview from Enquirer article ‘Avondale: breaking the cycle of revenge’. Comments, what can you relate to? Remind of clay. http://archive.cincinnati.com/article/20121028/NEWS/310280054/Avondale-Breaking-cycle-revenge

Move –

- Get up and write some graffiti on the board about your feelings of revenge. Any comments?

Mellow –

- This is a meditation to let go of revenge. Imagine the target of your anger or revenge: Now a white light covers this person/thing so you no longer can see them. You are now by yourself, and free of that person/thing. Let yourself feel your own freedom. Let yourself be surrounded by white light, and love.

Up –

2.Play second half of video ‘Avondale: breaking cycle of revenge’ about positive mindset and life changes

Psych Ed –

Anger is about feeling someone or something of value has been taken from you. Can be from any kind of loss – death, your childhood, trust in others. Can also come from being treated unfair, not having enough, feeling a lack of power & control. Sometimes it is about covering up other emotions: acting tough vs fearful, proving not weak, surviving. Problem is it’s like a bottle of pop. If builds up, explodes. If numb out, goes flat. Want to ease it off.

Self/MMM Group – ‘Tough Times’ Table